Nelson, Colleen. Sadia. Dundurn., 02/2018. 240 pp. $12.99. 978-1459740297. (ADDITIONAL PURCHASE). 10+

Nelson, Colleen. Sadia. Dundurn., 02/2018. 240 pp. $12.99. 978-1459740297. (ADDITIONAL PURCHASE). 10+

Sadia came out in February of this year, just after the formal release of young adult novel American Heart by Laura Moriarty, following controversy in fall of 2017. Much of the conversation around American Heart had to do with a white savior narrative, white gaze and lens, and reduction of a character of color to a device in order to enlighten and give complexity to a white character. This is all apart from giving an accurate depiction of Islam and of an Iranian woman. I cannot comment on the novel, given that I have not yet read it, but it is in our queue. Public opinion and reviews by other Muslim readers haven’t encouraged me to put it high on our list.

Enter Sadia. I asked a Muslim author if she had read this book yet, and we talked a bit about American Heart, white gaze and who should tell our stories. We talked about own voices; we talked about colonized minds and internalized racism and what happens when an “own voice” becomes a voice that oppresses. Sadia is a book by a white, Canadian author, Colleen Nelson, who is a teacher librarian in an elementary school. She has also worked with refugees.

Nelson reflects a bit in her blog about why she decided to write Sadia and what it meant for her to try to publish a book that was not an own voice. It is disappointing to see that she was worried that her book would not get published because more ownvoice/diverse authors are publishing books. Ultimately she did it for her students to be able to see themselves and to fill a void in her library, and hopes that there are many more published stories by Muslim writers in the future.

In the novel, fifteen-year-old Sadia has lived in Winnipeg for the last three years. Her family left Syria, shortly before the war. Though she has had time to acclimate to her life in Canada, high school means even more confusing changes.

Particularly jarring for Sadia is the behavior of her best friend Mariam, whose family relocated to Canada after the Arab Spring in Egypt. Mariam has been Sadia’s best friend from the first day they met. They even started wearing hijab around the same time. But this year is different. Mariam “de-jabs,” taking off her hijab during school, and putting it back on at the end of the day before going home. Mariam has also been distant, and her behavior has Sadia questioning the entirety of their friendship, which is made more complicated by her own friendship with Josh, Mariam’s crush.

Josh and Sadia are also trying out for the school’s co-ed basketball team, which Sadia desperately wants to be on. When Sadia makes the team her skill and passion is obvious, but playing basketball with hijab is more difficult than she had thought. Its especially disconcerting when she finds out that she may not be able to play in regulation games with it on.

Sadia is asked to help a new student acclimate to high school, Amira, whose family has recently relocated to Canada from Syria, under entirely different circumstances from her family. Thinking about the circumstances of Amira’s family fleeing Syria make her uncomfortable and the ideas Amira has about growing up Muslim in Canada have Sadia questioning her identity and how much she has already given up.

As someone who wears a headscarf on a daily basis, and has dealt with every day travails of scarf slippage and the like, I can identify with Sadia’s headscarf issues, but mostly I felt irritated with how hijab was given an impish, quirky quality where the Sadia cannot “take a jump shot without the bottom of the scarf flying in my face,” (p. 25). or where her arm catches her hijab and falls into her eyes (p.23), or where Sadia has no peripheral vision (p. 26).

Mostly, I wondered (with consternation) why athletic Sadia didn’t have an Al-Amira hijab, often considered training scarves for beginner hijabis and ideal for athletic activities. Another reviewer pointed out that access may be an issue, so I give them props for taking that into consideration. Though not always true, it is a significant plot device that will give non-Muslim and non-scarf wearing readers a window into what someone who wears a headscarf may have to deal with. And though we have seen many women compete in sporting events over the years wearing hijab, it was only last year that International Basketball Federation (FIBA) overturned a ban on head coverings. If you want to learn more about a young Muslimah basketball player, watch this video about Bilqis Abdul-Qaadir, teaching Muslim girls how to play basketball.

There an omission in the text, where Sadia refers to her grandmother as Teta (p. 38) and then on the following page uses the word Sitta. Both are correct, and sometimes used interchangeably (according to Hadeal and Sara), but without context, readers may be confused. Some of the turn of phrase is awkward as well. On page 78, Sadia says, “I could feel a blush spreading under my hijab.” I’m not sure why Nelson does not say, “I could feel a blush spreading across my face,” instead, as Sadia doesn’t cover her face. I took issue with the idea of Sadia and Amira never having touched snow (p. 48), when it does snow in Syria though infrequently, it is unlikely that both have never touched it. At the end of the book, a student exhibit has a silver collection plate used to collect donations from attendees. This collecting funds is compared to the concept of zakat, a form of alms-giving treated in Islam as a religious obligation, one of the five pillars of Islam. It would be more accurate to compare this to giving to sadaqah, or voluntary charity.

There are many times in the book where the relationship between Sadia, Mariam and Amira on occasion, is reduced to hijab. Some of that is oversimplification and equating Islam with hijab, some of this looks familiar to reactions to “de-jabbing” in the Muslim community, and some general adolescent issues, where one could substitute hijab for any other thing that might drive a wedge in a friendship. The two also have a conversation about being judgemental and hypocritical. A positive is that problems between Sadia and Mariam are also solved by them, there is no intervention by a white character, or a male character. Nelson captures growth and adolescence well, with characters pushing against boundaries, though these boundaries feel much younger than high school.

Headscarves and Hardbacks blogger, Nadia, points out that the framing of hijab and forced modesty is problematic in the book, because ultimately parents are forcing head scarves on their daughters and daughters cannot be modest without one. A conversation about hijab occurs in class where Mariam says, “It’s a hijab, a head covering. A woman’s hair must be covered, according the Qur’an.” Then, when the student questions why she doesn’t wear one she says, “it’s a personal choice” (p. 107-108). Though this is a reality for some Muslim girls and a majority of Muslim scholars, having all characters define hijab this way, as a required heading covering at all times, is oversimplified.

Sadia and Mariam also feel discomfort and guilt in interacting with Amira and realizing that they have had privilege in their relocation, coming to Canada as non-refugees. Sadia’s familial conversations about Syria are inconsistent. They talk about helping relocated Syrians early in the text, but when the family discusses those unable to leave, Sadia’s brother Aazim says, “It’s a war. That’s what happens. Innocent people suffer.” This struck me as rather callous. Similarly Mariam does not seem to reflect much on leaving after the Arab Spring in Egypt. Both families are not particularly proactive until the end of the book.

Nelson does capture some issues well. There are Islamophobic experiences that involve Sadia and her mother, one involving stares on the bus and another with a woman that tells Sadia’s mother, if she “wanted to stay in Canada, I should be Canadian and stop dressing like a terrorist.” Sadia reflects on if students in her class might feel the same way. There is also some self-realization in the book, where Carmina, Sadia’s Filipino-Canadian friend, wants to create a graphic novel featuring a Filipino character because she hates that there aren’t books with characters who look like her. Mariam wants to be both Muslim and Canadian, and while one should be able to be both, this sentiment captures the feelings that many Muslims have over having to choose identities and what that means in terms of cultural loss and normalization of “western values.”

Overall Sadia’s teammates feel genuine and have depth, even if on occasion they are used as devices. Alan is given depth with the revelation that his brother Cody has cerebral palsy. Nelson also has placed a male Muslim character on Sadia’s basketball team, but there is no interaction between the two of them. His primary function being to be on the basketball team and to tell Josh that there was no hope for him in being allowed to date Sadia. Despite the sports trope, with the opposing team depicted as unsportsmanlike racists, it is moving to see Sadia’s team and the spectators cheer for her and advocate for her to play, on top of Sadia and her parents separately advocating for her religious rights as a Canadian citizen.

So what is my overall verdict for this book? There is definitely a didactic and educator positive feeling to this book, promoting the idea that a really good teacher can have the power to foster empathy, create nuanced conversations and give students agency. Teachers are also presented as people who make mistakes. Yet, this book has its own mistakes and I still struggle to see, between a Muslim and non-Muslim reader, whose gaze is most important. Sadia gives non-Muslim readers a glimpse into the lives of several Arab Muslim characters with a level of complexity to their personalities. It allows Muslim readers to see a few pieces of themselves, with some amount of accuracy, though I do wonder if any Syrian Muslim readers vetted this book prior to publication.

I would argue that the tone of the book, and the level of conflict make the book feel younger than a typical YA book, and could have been targeted to younger readers. Still, it is a solid entry point for readers who want a basketball-playing, hijab-wearing protagonist in a coming of age story because, as far as we know, those don’t exist yet. Are there better books about Muslim identity by Muslim authors? Yes. If you do add this book to your collection, don’t let this narrative be the only one your readers will get.

Mafi,Tahereh. This Woven Kingdom. Feb. 2022, 512 pp. HarperCollins, $19.99. (9780062972446). Grades 9 – 12

Mafi,Tahereh. This Woven Kingdom. Feb. 2022, 512 pp. HarperCollins, $19.99. (9780062972446). Grades 9 – 12 This review was originally published in

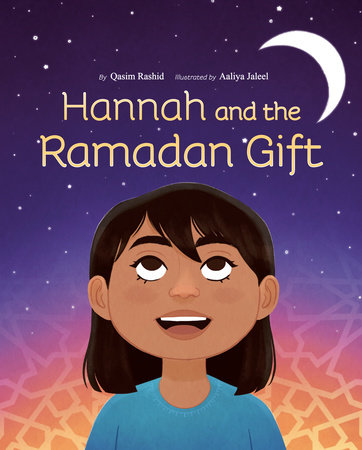

This review was originally published in  Gr 1-5- At eight years old, Hannah’s family says she is too young to fast from dawn to sunset through the month of Ramadan, but Dada Jaan has an idea of how Hannah can help. He says that Ramadan is a reminder to Muslims to help those in need and helping neighbors is worth the world. In her independent actions in school and at home, the girl finds that helping is more difficult than it seems. At the end of Ramadan, celebrating with her religious and ethnically diverse community, Hannah wonders what, if any, impact her actions have made and whether it is enough. Human rights activist, attorney, and former candidate for Virginia State Senate Rashid’s narrative shows the positive and local action children can take and the wisdom and kindness gained through learning from elders.

Gr 1-5- At eight years old, Hannah’s family says she is too young to fast from dawn to sunset through the month of Ramadan, but Dada Jaan has an idea of how Hannah can help. He says that Ramadan is a reminder to Muslims to help those in need and helping neighbors is worth the world. In her independent actions in school and at home, the girl finds that helping is more difficult than it seems. At the end of Ramadan, celebrating with her religious and ethnically diverse community, Hannah wonders what, if any, impact her actions have made and whether it is enough. Human rights activist, attorney, and former candidate for Virginia State Senate Rashid’s narrative shows the positive and local action children can take and the wisdom and kindness gained through learning from elders.  Jaleel’s palette of saturated pinks, purples, yellows, and aqua conveys the passage of time through the month while tying in common Islamic geometric patterns and decor. Language and visual markers indicate Hannah and her family are South Asian and an author’s note describes Eid with family and community in Pakistan and in the United States. Though this narrative is accessible to all Muslims and non-Muslim readers, it particularly reflects Rashid’s Ahmadiyya Muslim values in service to humanity, peace, and love of mankind.

Jaleel’s palette of saturated pinks, purples, yellows, and aqua conveys the passage of time through the month while tying in common Islamic geometric patterns and decor. Language and visual markers indicate Hannah and her family are South Asian and an author’s note describes Eid with family and community in Pakistan and in the United States. Though this narrative is accessible to all Muslims and non-Muslim readers, it particularly reflects Rashid’s Ahmadiyya Muslim values in service to humanity, peace, and love of mankind.

K-Gr 2–Amira feels conflicted when she realizes that school picture day is the same day as Eid. Spotting the crescent moon marking the end of Ramadan, Amira and her brother Ziyad know it means that there will be prayers, celebrations, and skipping school the following day. Amira’s mom decorates the girl’s hands with mehndi. Amira and Ziyad prepare goody bags for the kids at the masjid, while her mother irons Amira’s Eid outfit, a beautiful blue and gold mirrored shalwar kameez.

K-Gr 2–Amira feels conflicted when she realizes that school picture day is the same day as Eid. Spotting the crescent moon marking the end of Ramadan, Amira and her brother Ziyad know it means that there will be prayers, celebrations, and skipping school the following day. Amira’s mom decorates the girl’s hands with mehndi. Amira and Ziyad prepare goody bags for the kids at the masjid, while her mother irons Amira’s Eid outfit, a beautiful blue and gold mirrored shalwar kameez.  Though Eid is full of the joy and community she loves, missing picture day puts a damper on the celebration, until Amira thinks of a possible solution. Deceptively simple, Faruqi’s narrative gently addresses the impact that the celebration of non-dominant cultures and holidays has on children and choices families make to uphold traditions. Moreover, Amira’s conflicted feelings and insistence on finding a solution create opportunities for dialogue about the importance of acknowledging spaces that matter to children, especially while families try to foster positive identity. Azim’s illustrations are fun and colorful, with tiny details reflecting the family’s personality, while the people attending Eid celebrations at Amira’s masjid are racially and culturally diverse, with varied skin tones, body types, and expressions of fashion and style.

Though Eid is full of the joy and community she loves, missing picture day puts a damper on the celebration, until Amira thinks of a possible solution. Deceptively simple, Faruqi’s narrative gently addresses the impact that the celebration of non-dominant cultures and holidays has on children and choices families make to uphold traditions. Moreover, Amira’s conflicted feelings and insistence on finding a solution create opportunities for dialogue about the importance of acknowledging spaces that matter to children, especially while families try to foster positive identity. Azim’s illustrations are fun and colorful, with tiny details reflecting the family’s personality, while the people attending Eid celebrations at Amira’s masjid are racially and culturally diverse, with varied skin tones, body types, and expressions of fashion and style.

Back matter features an author’s note and glossary of terms, referencing Urdu and Amira and her family’s Pakistani roots.

Back matter features an author’s note and glossary of terms, referencing Urdu and Amira and her family’s Pakistani roots. Muslims in Story: Expanding Multicultural Understanding Through Children’s and Young Adult Literature

Muslims in Story: Expanding Multicultural Understanding Through Children’s and Young Adult Literature

This review was originally published in the November/December issue of Horn Book magazine and can also be found on the

This review was originally published in the November/December issue of Horn Book magazine and can also be found on the  This review was originally published in the November/December issue of Horn Book magazine and can also be found on the

This review was originally published in the November/December issue of Horn Book magazine and can also be found on the  This review was

This review was  Nelson, Colleen.

Nelson, Colleen.  Alexis (Rabiah) Lumbard York is an author of mostly children’s picture books that are aimed at younger readers, but reach readers of all ages. Many of York’s tales have Middle Eastern origins but transcend religious labels, conveying an ethereal sense of the divine that is be accessible to children of many religious and non-religious backgrounds. For more information about York, please visit her

Alexis (Rabiah) Lumbard York is an author of mostly children’s picture books that are aimed at younger readers, but reach readers of all ages. Many of York’s tales have Middle Eastern origins but transcend religious labels, conveying an ethereal sense of the divine that is be accessible to children of many religious and non-religious backgrounds. For more information about York, please visit her